"Sign from anywhere, on any device." It's the golden promise of modern e-signature platforms. Sales teams love it because it reduces friction; executives love it because it accelerates deal velocity.

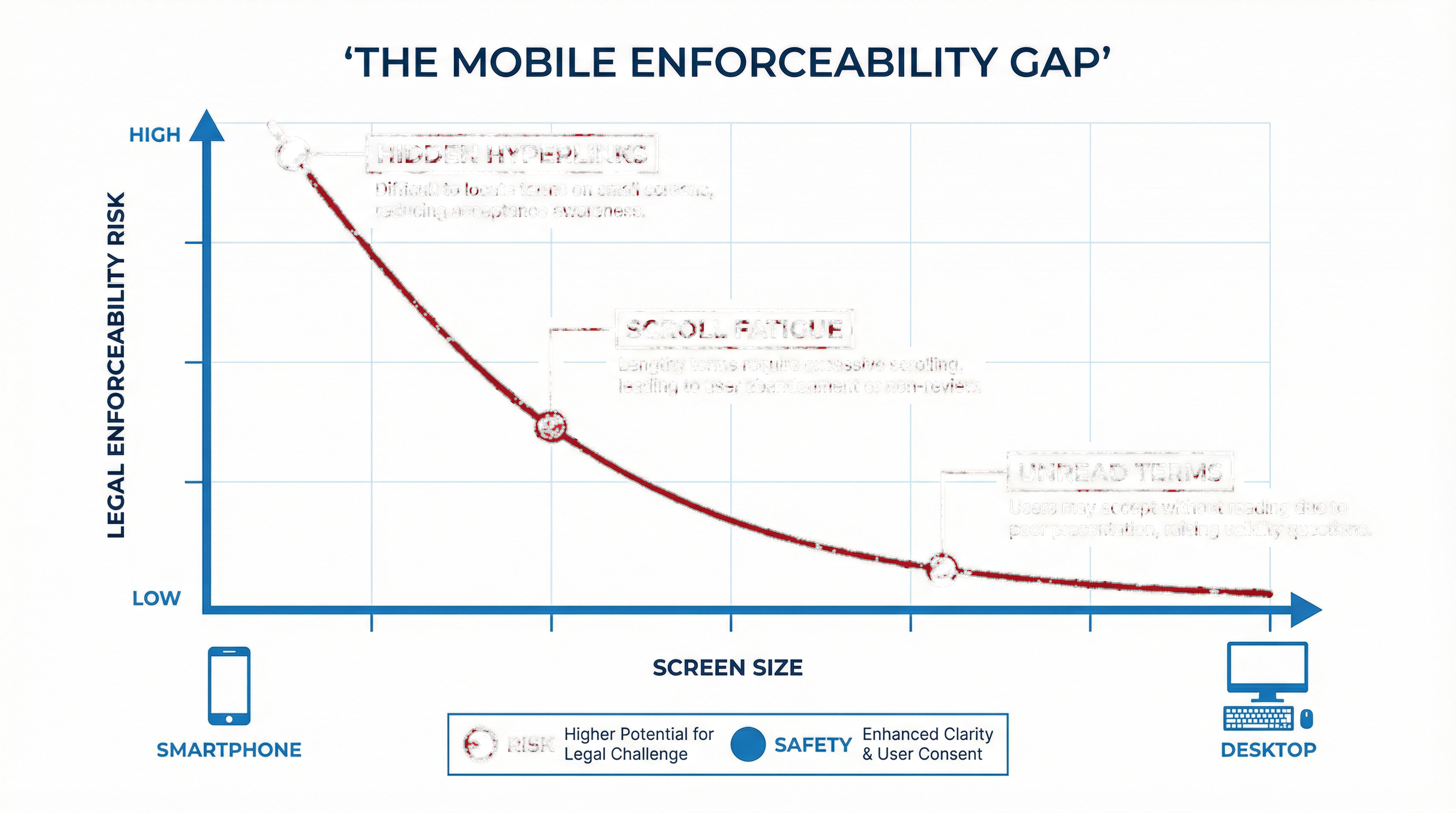

But there is a hidden legal cost to this convenience. As more B2B contracts are executed on 6-inch screens, courts are increasingly scrutinizing whether these interactions meet the standard of Constructive Notice.

This article explores a critical blind spot in procurement: the trade-off between user experience (UX) and legal enforceability. While a signature captured on an iPhone is technically valid under ESIGN/eIDAS, the context of that signature can render the entire agreement voidable.

The Core Legal Concept: Constructive Notice

For a contract to be binding, the user must have "actual or constructive notice" of the terms. On a desktop, a hyperlink is usually sufficient. On a mobile device, however, if that hyperlink is pushed "below the fold" or obscured by a sticky "Sign Now" button, courts may rule that the user never effectively saw the terms.

The "Small Screen" Defense

Recent litigation trends show a rise in what defense attorneys call the "Small Screen Defense." In cases like Cullinane v. Uber Technologies [1] and Meyer v. Uber Technologies [2], the central argument wasn't whether the user clicked "I Agree," but whether the design of the mobile interface made the terms conspicuous enough.

When a 50-page Master Services Agreement (MSA) is condensed into a smartphone viewport, two things happen:

- Visual Clutter: The "Sign" button often dominates the screen, visually overpowering the link to the Terms of Service.

- Scroll Fatigue: Users are statistically far less likely to scroll through a long document on mobile than on desktop.

Why "Clickwraps" Fail on Mobile

Not all "I Agree" buttons are created equal. In the desktop era, a "Browsewrap" (where terms are just a link at the bottom) was deemed insufficient, while a "Clickwrap" (where you must check a box) was the gold standard.

On mobile, even Clickwraps are failing. If the checkbox is pre-checked, or if the "Terms & Conditions" link is too small to be easily tapped with a thumb (a "fat finger" error), courts have refused to enforce arbitration clauses and liability waivers.

The Risk for Procurement: If your sales team is pushing clients to "sign on the go" using a tool that prioritizes speed over disclosure, you may be collecting signatures that are legally worthless in a dispute.

Consultant's Recommendation

As outlined in our Strategic Guide to Procurement, you must evaluate the mobile signing experience of any vendor you consider.

Do not just look at how easy it is to sign. Look at how hard it is to miss the terms.

- Test the "Thumb Zone": Can you easily tap the "Terms" link without accidentally hitting the "Sign" button?

- Check for "Scroll-to-Accept": Does the platform force the user to scroll to the bottom of the document before the signature field becomes active? (This is a strong defense against the "I didn't see it" argument).

- Avoid "Sign-in-Wraps": Ensure that the act of signing is distinct from the act of logging in.

References

[1] Cullinane v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 893 F.3d 53 (1st Cir. 2018). The court found that the design of the screen did not provide reasonable notice of the terms.

[2] Meyer v. Uber Technologies, Inc., 868 F.3d 66 (2d Cir. 2017). A contrasting ruling where a cleaner design was found sufficient, highlighting the importance of UI specifics.